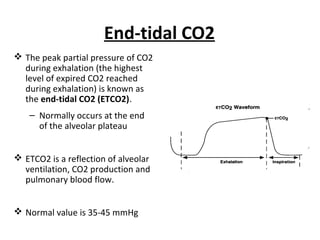

Depending on the situation, the actual waveform of the capnogram and/or the end-tidal value at the end of exhalation may help us with more than just determining hypoventilation in patients undergoing procedural sedation in the emergency department. The discrete end-tidal number we refer to is the value at the end of phase III, the very end of expiration prior to inhaling the next breath. The waveform then plateaus during phase III, with slight increases in the CO2 concentration from alveolar air. Once the patient begins to exhale (phase I), the initial expired air is predominantly dead space with little expired carbon dioxide (CO2), but as the more densely concentrated CO2 is expired, there is a sharp increase in the end-tidal waveform that represents phase II. Phase 0 begins during the inhalation phase of the respiratory cycle and the capnogram drops precipitously from its peak level at the end of expiration. The end-tidal capnogram is separated into four separate phases (see Figure 1). End-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) sensibly correlates with the pathophysiology of those and many other disease processes and can help guide decision making on your next shift.

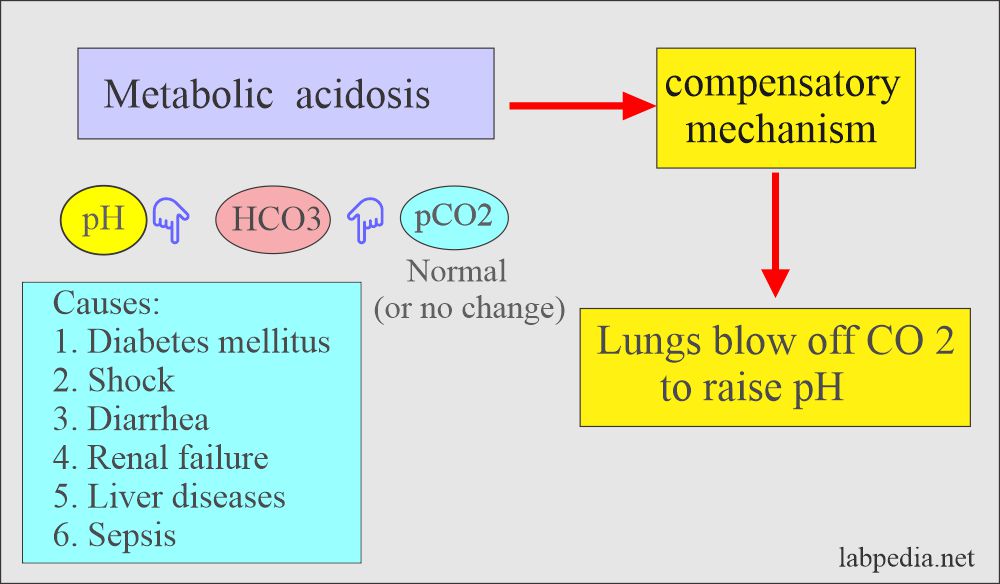

Are the chest compressions being performed on your cardiac arrest inadequate? Should you stop resuscitation efforts? Is your hyperglycemic diabetic in diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA)? Is that nasogastric tube in the stomach? End-tidal capnography can lend insight to these questions that emergency physicians encounter on a daily basis. It can quickly and efficiently answer clinical questions beyond that of sufficient ventilation. 1 It can identify hypoventilation earlier than other monitoring tools we have at our disposal in the emergency department, but its utility doesn’t end there. End-tidal capnography has gained momentum over the years as a standard for monitoring patients undergoing procedural sedation in the emergency department, with a level B recommendation coming out of ACEP’s clinical policy regarding procedural sedation in 2014.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)